At the end of July we took a family trip to Jerusalem, with our main goal to visit the Israel Aquarium. Both the aquarium and the neighbouring Biblical Zoo counterpart have been on our lists for a while, but we rarely make it to Jerusalem ever since Amir was born. As such, we hyped up the trip quite a bit and were rather eager to go. Despite it being summer, we found parking quite easily outside the complex and within minutes we were buying tickets and heading inside. The cheery ticket checker recommended that we start our tour with a visit to the butterfly house and gardens, an unusual addition to an aquatic attraction.

Passing through the double doors, we were dumbfounded by the size of the butterflies flapping languidly around us. Huge navy and cobalt wings operated in synchrony as the large blue morpho butterflies, native to Central America, fluttered around us. Amir was tempted to try and catch them, but we led by example and observed only. There were a handful of other species as well, flying or resting along the attractive “jungle” path. Overall, the butterfly addendum was an unexpected but welcome addition to our trip itinerary.

Moving on to the main attraction, we left the butterflies and entered the main building which houses the aquarium. Darkness enveloped us, as did the dozens of other visitors who shared in our experience. Huge fish tanks greeted us as we passed into the first exhibit, filled with countless specimens of wriggly sea creatures all wiggling about in their aquatic environs.

I appreciated how each exhibit followed a particular theme, all focusing on the fishy elements. That first gallery was dedicated to the four “seas” of Israel – the Mediterranean, Red, Dead and the Sea of Galilee – each with its marine life. I was pleasantly surprised to learn about the Dead Sea toothcarp, which can’t live in the intense salinity of the lake itself, but rather lives in the desert streams that feed into the Dead Sea.

Naturally, much of the fish featured are native to the Mediterranean, so a few of the subsequent exhibits focused on Israel’s western seaboard. There was also an exhibition about fish in the Suez Canal, which has had an ecological impact on the Mediterranean with invasive species swimming over from the Red Sea. Within the darkened halls of illuminated tanks, fish of all varieties, sea horses, a one-armed sea turtle and a pool of rays and guitarfish really fleshed out the collection.

There were a few aquarium tanks that were designed to look more realistic, matching the habitat’s general appearance with paint and sculpted rocks. The Mediterranean coast tank even featured choppy waters, mimicking the natural movement of the sea. I quite enjoyed this, feeling like I was looking at a living diorama, but ultimately the photographs failed to convey the joyous sensation.

Speaking of dioramas, there were several exhibits which had special tanks featuring tunnels which allowed visitors to view the fish from the inside. These were naturally very popular with the children, so I had to be quite patient to get a picture of Bracha and Amir posing “underwater” with the fishy friends. The tank’s “actinic” blue lighting takes some getting used to in person, and some efforts to balance out when editing the photos (of which I’m not entirely satisfied by).

And then there were sharks! We reached a glass tunnel walkway under a big tank where sharks passed over, swiftly and with the fluidity apt for such apex predators. Amir tried befriending one shark, which appears to be a sand tiger shark, but it swam off without as much as a passing nod. Unfortunately, I didn’t see any signs identifying which shark species were in the large tank, but the marvels of technology today greatly helps.

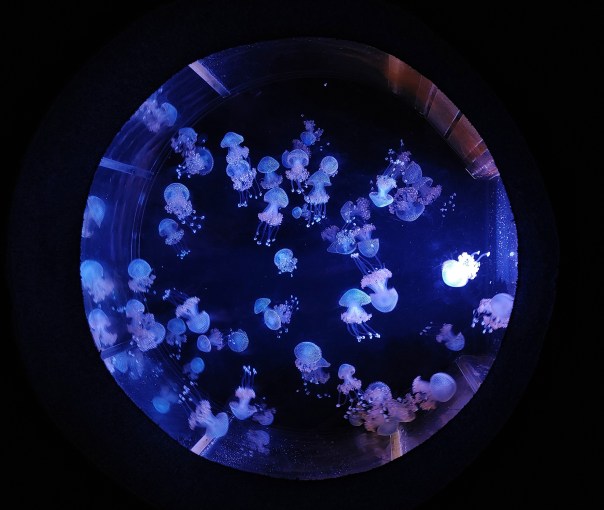

Around the corner we found a huge glass panel and stadium seating where people can sit and watch the wildlife as if it was a film in the cinema. We sat for a few minutes and had a bite to eat before continuing on to see some jellyfish. In fact, I was quite surprised at how many jellyfish the aquarium has, all drifting about in their little colourful tanks. Some like the moon jellies and Australian spotted jellyfish certainly made for easy, artsy photography.

I would be amiss if I did not mention the fish-related art installations that decorated the entrance and exit of the aquarium circuit. There was even a little information regarding kashrut and kosher fish, for hungry visitors looking for a cheeky bite to eat in the darkened exhibits.

As we were leaving the building, I noticed that there was a side exhibit dedicated to the suspended skeleton of Sandy, a dead fin whale that washed ashore back in 2021. The huge skeleton, measuring 17.5 metres (57 feet), made the room feel small – and an elevated platform was needed to be able to get a good look at the alien-looking skull bones.

When I climbed back down, we gathered our belongings and made our way out of the aquarium, feeling happy to have seen this long-awaited site. We then drove to get some lunch at one of Jerusalem’s acclaimed pizza shops and then the drive back home to Elkana at the edge of the Shomron.