A few weeks ago, in the middle of August, Bracha and I enjoyed a nice trip to the Hai Bar Carmel nature reserve, located on Mount Carmel. A part of the overall Mount Carmel national park, this small reserve is notable for its breeding and rehabilitation program that helps repopulate the country’s vulture and deer populations. Even though I had been to various parts of Mount Carmel – and certainly Haifa itself – I had not yet stepped foot into the famous Hai Bar. Thankfully, while making extended weekend plans up north at my folks’ place, the idea to visit came up and we made it happen.

Taking in our scenic surroundings

Getting to the park was relatively simple on paper, and it was just a single bus ride from the nearest Haifa train station. We had packed smartly, with just two backpacks, and disembarked just outside of Haifa University ready to conquer any trail in our path. But before any conquering could be done, we stared out at the sweeping view of the tree-covered mountain that tapers off into the cool Mediterranean Sea. We could see roads and trails snaking down the slope below us, but we did not know quite where to go. Navigating with the help of Google Maps, we set off on a rural road that took us on a long, winding route all the way to the Hai Bar reserve.

Bracha taking in the view

There were a few highlights along the way, deserving of mention, before we reached the reserve’s open gates. First, the largest Schneider’s skink I had ever seen appeared in front of us and slithered under a large boulder. I was desperate to catch it with my camera so I crouched down and snapped some shots, catching only a bit of its tail with my extended lens. Upon examining the photos later, I noticed that there were shed snakeskins, ghostly remains of a snake that once found shelter during its moulting session. Unfortunately, I hadn’t noticed it while we were there and, although I tried my best, experts informed me that there was no definite way to identify what snake species left behind that papery memento.

T93 making a pass overhead

As we trotted down the gradient road, chatting softly into the wind, Bracha excitedly pointed to a large bird of prey slowly rising from the woodlands before us. It was a griffon vulture – the first of the day – and one of the largest raptors found in Israel. Our trot picked up in speed as we made our way towards the soaring vulture, and before we knew it, we were passing through the park’s reception-office. Immediately outside the office-gift shop is a large wooden balcony overlooking the same majestic view that we had been enjoying ever since we had gotten off our bus.

The balcony

Next, we found a small theatre of sorts where a short nature film about the reserve and its unique role was playing. As mentioned before, the reserve runs breeding and rehabilitation programs for vultures and deer. Vultures in the wild face the ever-present danger of poisoning, where ranchers, or perhaps other parties, poison carcasses in efforts to curb predatory attacks on their flocks and herds. This can potentially be a death blow to a large chunk of the ecosystem, as many animals – big and small – feed from carrion. The lives of many vultures in Israel have been lost due to this senseless approach, but that’s not the only danger they face.

The vulture cage

Another big one, which affects eagles and other large raptors as well, are unprotected power pylons which can electrocute the birds instantaneously should they accidentally make contact with two sections simultaneously. In efforts to curtail the damages done by poisoning, the National Parks Authority operates several feeding stations where “safe” carcasses are deposited as an easy buffet for carrion-loving creatures. The electrocution issue remains to this very day, with only some of the deadly pylons suitably refitted with protective shields by the Israel Electric Company.

Persian fallow deer in the enclosure

In regards to deer, the main issue had historically been over-hunting, and it was a well-thought out plan to reintroduce deer species that had since disappeared from the wild in Israel. One such species was the Persian fallow deer, whose new population partly originated in an elaborate smuggling operation bringing a handful of female does via the last El Al flight out of Tehran before the Islamic Revolution which soured diplomatic relations. I warmly recall seeing one of the released descendants of these deer in Nachal Kziv, one of the Mediterranean habitats chosen to host renewed deer populations. Another example is the roe deer, a species which once populated the Carmel region and whose repopulation project was launched in 1996. Sadly, I have no warm memories of any roe deer of any kind, but that might change one day.

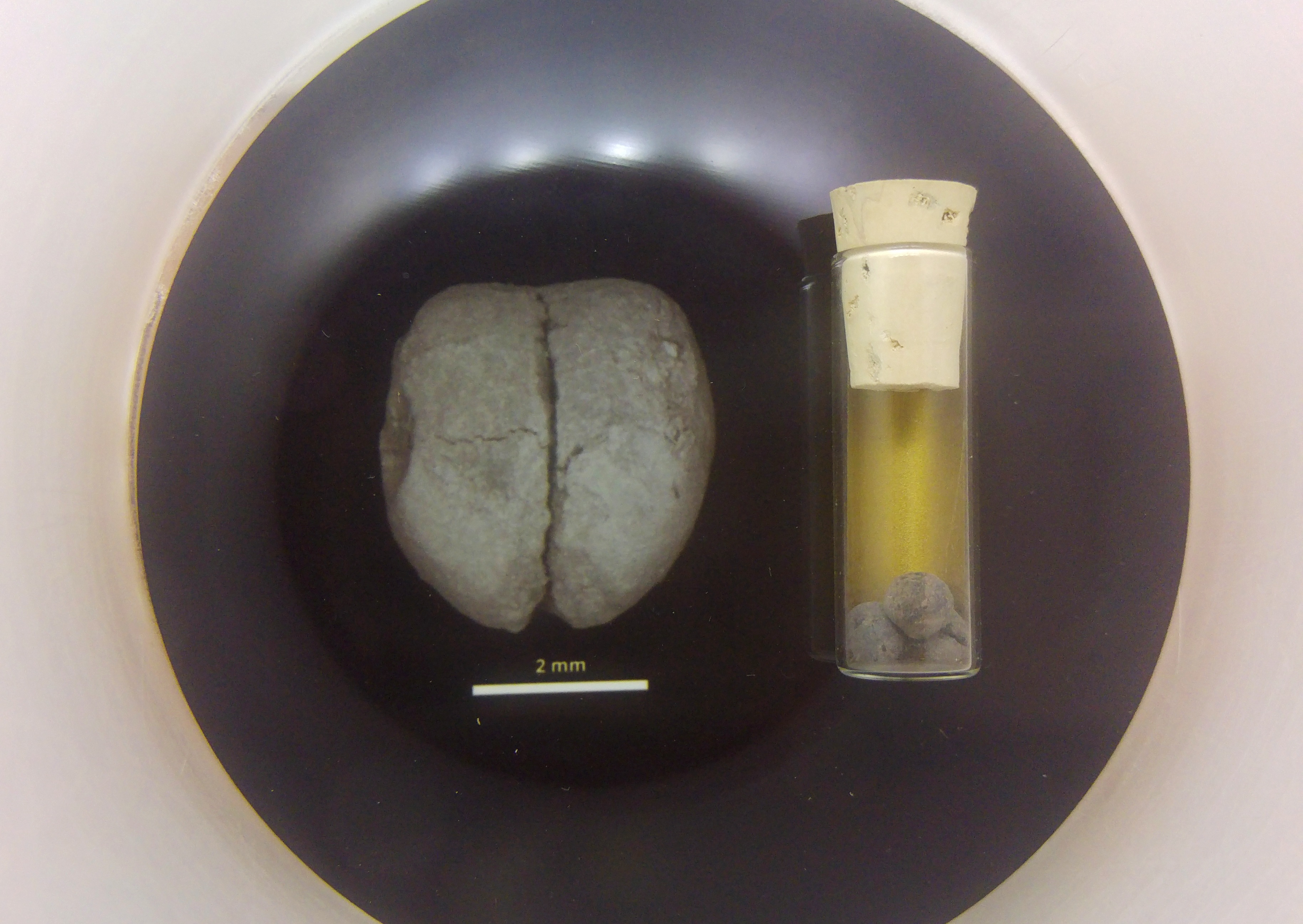

The dried fire salamander breeding pool

As would be expected, part of the reserve is fenced off plots of land where these animals live, at least for now. We saw, in addition to the aforementioned fallow and roe deer species, a small herd of wild goats ambling about in a shaded yard. Despite their wild-sounding name, these are, in fact, domesticated goats, and as such, there are no plans to release them into the wild. It was delightful seeing all the even-toed ungulates minding their own business in their enclosures, but there were more exciting things to be seen and so we kept going. One notable feature is the fire salamander breeding pool, built to help bolster the Mount Carmel population of this incredible species – of which I have only ever seen tadpoles, when I visited the Sasa Museum several winters ago. Interestingly enough, this is the southernmost population of this species in the entire world, so this pool – dry in the summer months – must be doing a good job.

The feeding station on the opposite slope

The highlight of this visit was undoubtedly the vultures, and as we approached the hallowed lookout, from which so many photos are taken, we could see the soaring griffons casting great shadows on the gentle slopes below. A caged white-tailed eagle distracted us temporarily, but we tore ourselves away and reached the lookout. I was agape as I took in our surroundings – from the rehabilitation cage stocked with both griffon and Egyptian vultures, to the countless soaring vultures and the eye-catching feeding station on the opposing slope.

T36 being friendly

First, we acknowledged the rather friendly griffon vulture tagged “T36”, who stood on the cage and watched us in a carefree manner. According to the experts, “T36” was born in the Hai Bar Carmel’s breeding facility and released into the wild in 2012. Another friendly griffon, tagged “T60” was also locally born and released in 2013. Other, more wild griffons soared at a safe distance – most of them without any tags or other identifiable markers. The tedious photographing of the twenty-thirty vultures provided just one other griffon that had readable tags – “T93”, who was surprisingly born and transplanted from Catalonia, and released in the Golan in 2019.

Griffon vultures at the feeding station

As mentioned, the feeding station across the wadi took a lot of my focus, as I attempted to photograph everything that moved at that great distance – hoping to catch some Egyptian vultures and common ravens. Only the latter made an appearance, which provided some excitement to the already exciting time we were having. Another winged creature was spotted standing atop of an old cow carcass – a lone cattle egret, perhaps mourning his namesake. It suddenly dawned on me that this is the feeding station that is live-streamed on YouTube, highlights of which I had watched here and there in recent years (see HERE for more). I quickly pulled out my phone and found the ongoing live-stream, hoping that there’d be something exciting happening on-screen. Alas, just the mopey cattle egret graced my screen, but I thought the concurrent watching of the station – both in person and online – to be too eventful not to share.

Screenshot of Vulture Feeding Station 1 courtesy of Charter Group Birdcams

We watched the vultures soar, land and take off until we figured that it was time to move on with our day. I was sad that no free-flying Egyptian vultures were seen, but the sheer quantity of griffon vultures was so unexpected that I felt more than pleased with what we had seen. We made our way back out of the park, hitching a quick ride to the main road before heading over to the adjacent Haifa University to get our bus. As we began the journey back down Mount Carmel and towards our target train station, we watched the novel and not-yet-opened cable car system that looks quite enjoyable as a means of public transportation. It’s slated to open to the public in October, so we have to be patient until we can ride the great swinging orbs up and down the famed mountain of old. Thus ended our trip to the fascinating Hai Bar Carmel, where nature gets a second chance – and we get to watch.