Despite my increasingly busy life, I still consider birding to be one of my primary hobbies, albeit woefully neglected at times. In Israel, summer is regarded as the doldrums for birding, sandwiched between spring and autumn migration and lacking the wholesome verdancy of the wet winter season. However, that doesn’t mean that the land is wholly devoid of birds, one just needs to know where to look.

I saw that the Israel Birding Club had advertised an early June night birding tour to the Judean Desert around the Dead Sea, which is a known hotspot for some very special species of wildlife. One of the presumed target species is the Egyptian nightjar, one of three nightjar species that can be readily found in Israel. I had seen the most widespread species, the European nightjar both in Jerusalem and in Givat Shmuel, but the other two species remained elusive. This is not for want of trying, I had taken a stab at looking for Egyptian nightjars (and more) during the Eilat trip that Adam and I took back in 2019. That said, finding nightjars out in the open in the dark can be a bit difficult, so some professional guidance was certainly welcome.

Reaching out to Adam once again, we settled our plans and headed out in the late afternoon with a few stops in mind. We cut through the Shomron on Road 5, which later turns into 505, and began our descent into the desert. Thankfully, there was a roadside lookout which gave us the opportunity to take in the rural view, and the distinct mountaintop of Sartaba (Alexandrium). But with daylight counting down, we hurried back into the car and made our way down to Road 90 – Israel’s longest road which stretches from Metula until Eilat.

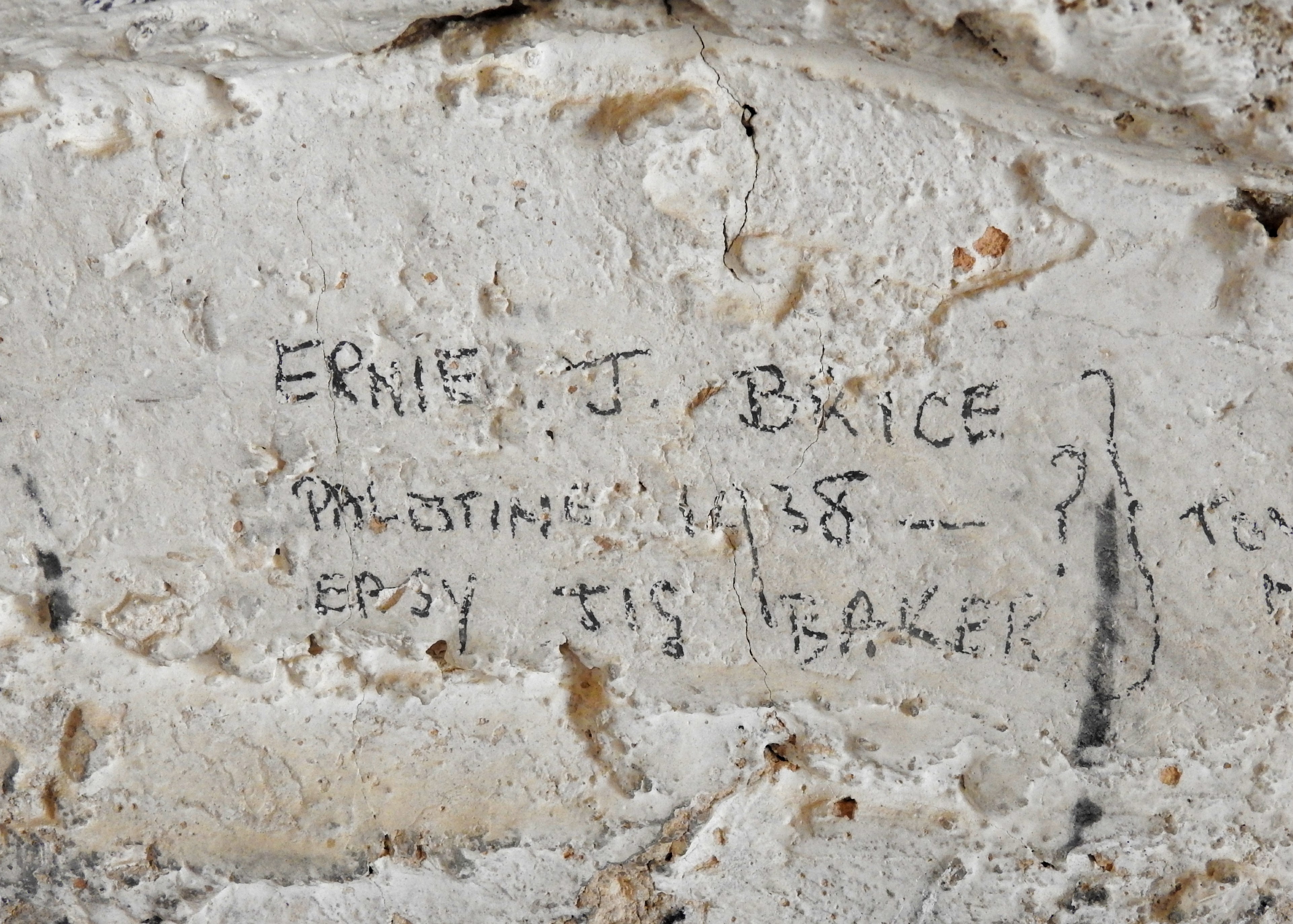

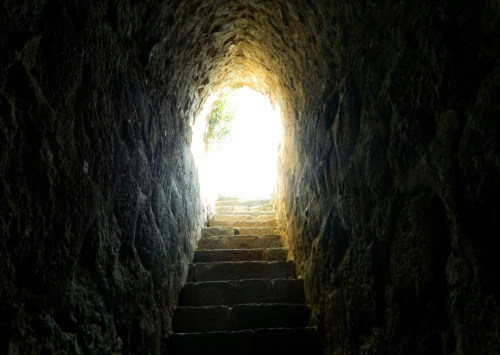

Our first real stop of the adventure was at an unassuming rest stop near Paza’el, where a hidden attraction can be found. Just south of the gas station, there is an old, abandoned complex surrounded by a fence – which happens to be breached in more than one place. This was a large crocodile farm, founded in the late 1980s as a tourist attraction, was closed during the First Intifada and then intended to be used to produce lucrative crocodile skin. Once laws were passed in 2013 banning the production of leather from such a designated protected species, the owner gave up and abandoned the project due to lack of funds. So now, twelve years later, hundreds of Nile crocodiles lurk in and around a small pond inside the complex, waiting for nothing but time itself.

Now just as an anecdotal sidenote, whilst drafting this blog post on my commute, I paused writing one morning with the previous sentence – and I had considered writing it a little differently, ending with “waiting for nothing but death.” Little did I know, that on that very morning there was an operation spearheaded by various governmental bodies to get rid of this “issue” at hand – namely, the culling of all 262 remaining crocodiles. Apparently, after numerous ideas were floated over the years, this seemed to have been the last resort. I was understandably shocked, but relieved that, at the very least, I was able to see this site before its bitter end. It had been somewhere on my figurative to-visit list ever since I had seen aerial drone photographs shared on Facebook by a young lad named Yair Paz (I can’t seem to relocate the post, but some other enchanting aerial footage can be seen HERE).

We entered through a breach in the fence, passing some excited youths along the dusty path, and began to survey our surroundings. I was amazed at the dense concentration of crocodiles slumped on the dirt banks of the small, murky pool. Conjuring up vivid terminology torn from the pages of the likes of HP Lovecraft, these cold-blooded reptiles certainly played the part of ancient foul beasts as they skulked motionless and ominously in the fetid waters, only their bewitching eyes tracking our moves. We took some pictures and marveled at the sights we were seeing – such an unexpectedly rewarding experience.

Headed back into the car, we drove south down the 90 until we reached Almog Junction, where the tour was meeting up. Daylight was fading fast as we introduced ourselves to the birding guide, Yotam Bashan, and received the briefing on where we were going and what we were anticipating to see. As expected, we started in search of Egyptian nightjars, driving out to some salty, dry watermelon fields outside of Kalya. I hadn’t thought much about it at the time, but a big concentration of caves up on the craggy cliffside to the west of the fields are heavily featured in my thesis research. Alas, I did not get any sufficient photos of the adjacent cliffs before we were plunged into nightfall.

Lights from the Jordanian side of the Dead Sea glittered over the placid waters as we began our hunt for nightjars. Several high-powered flashlights were employed to make our searches easier. It was explained that the best way to find the nightjars was by shining a bright light around, and looking out for glints in the darkness returning said light. Sure enough, it worked and before long there was a slight glint on the dirt road far up ahead, and it flew off before we got much closer.

Sometimes, the glints were generated from trash and debris, such as soda cans, but sometimes it was the real deal. We crept up on several nightjars, most of them taking flight before we had a chance to take any decent pictures. Since neither of us have proper DSLR/mirrorless cameras, we had an even bigger challenge. Interestingly enough, my best photograph of an Egyptian nightjar from that evening was of one doing a close flyby.

Our guide had beckoned these curious feathered friends with vocal calls broadcast over a small, portable speaker. When a nightjar fluttered by to examine, we all rushed through our camera buttons and tried desperately to get some snazzy pics. Photographic evidence aside, it was quite a surreal experience standing out in the dark in a dusty field, eerie calls playing over and over, ghostly bird shapes swooping around us – sometimes surprisingly close.

While the focus was clearly on the majestic nightjars, there were other creatures lurking out in the darkness. We spotted some stone curlews, mountain gazelles, a fox and perhaps a jackal too. When we had felt relatively satiated by our viewings, we walked as a group back to our cars and drove down a dark agricultural road to some nearby date palm plantations. Now, the focus shifted to something a little more familiar, the pallid scops owl. While this was to be my first sighting of this localised species, I had a number of fond memories of the bird’s relative, the Eurasian scops owl (THIS being my best picture to-date). Similar to the Egyptian nightjar, I had briefly searched for a pallid scops owl while down in Eilat and the Arava, as they can periodically be found sleeping in acacia trees.

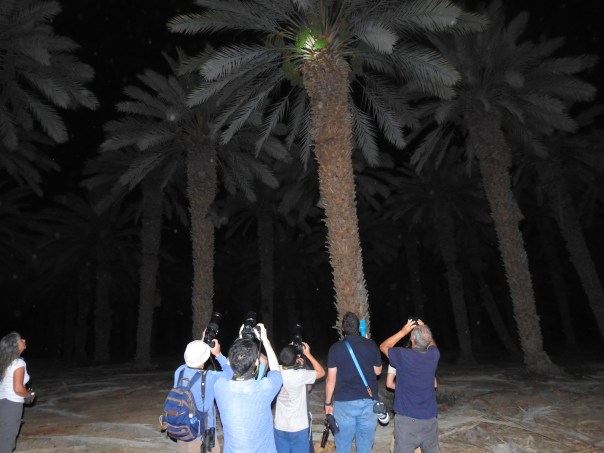

We entered the rows of hefty date palms, a rip-roaring game of lights and shadows happening all around us as our torches flickered about. The calls of the nightjar, still echoing in our ears, could be heard faintly off in the distance fields. Before long, after some tramping through fallen vegetation, Yotam spotted an owl. He directed us swiftly, guiding our hushed whispers towards an illuminated patch just below the arched fronds. Lo and behold, my very first pallid owl, its minuscule body tucked neatly in the tree’s rough undercarriage.

The owl posed pleasantly enough, changing positions once or twice before we decided that it was time to move on. Another owl or two were spotted, sometimes just a brief pale flurry as it disappeared into the darkness. We learned more about the owl, its interesting nesting techniques and the research that had gone into Israel’s population in recent years. With that, we climbed back into our vehicles and continued through the agricultural area until we turned back onto the 90 and drove south. Our next destination was a collection of agricultural fields and greenhouses by the saltmarshes of the Dead Sea.

We parked offroad near Nachal Qumran and began preparing for the search for an even more elusive Caprimulgus species, the Nubian nightjar. This species is smaller and has a more ruddy complexion, with small white wings flashes that make it easy to distinguish from its more pale relative. But, before we had the chance to properly mobilise, air raid sirens went off in the distance, and on some of our mobile devices. An incoming missile was detected, sent by our staunch Houthi fans in Yemen, and so we took shelter the best we could. Crouched in anticipation, I suddenly saw some flashes of light high up in the sky to the southeast, undoubtedly shrapnel from the intercepted missile. A few minutes later, when the danger had passed, we resumed operations and gathered up around our guide.

The search went exactly the same way as it had in the watermelon fields of Kalya, beams of lights strobing through the hot, dusty air. Thankfully, Nubian nightjars were available and we got plenty of sightings both on the ground and in the air, swooping as they hunted moths and other winged delicacies – as goatsuckers do. There was even one moment where one nightjar landed tantalisingly close to some of the tour members, but unfortunately for me, the angle and topography made photography a nightmare. Eventually, as we made our way back to the cars, a ranger from the Nature and Parks Authority came by to check out who we were. He said that he has been extra-vigilant lately with suspicious figures roaming around the Dead Sea shores, especially after some gun smugglers from Jordan were recently apprehended. With that, we buckled ourselves up and began the long drive back to our respective homes, pleased with the successes of our valiant efforts – and for me, three new “lifers” to add to my life list.