Riding on the coattails of my excursion to some fascinating sites around Nachal Tirza, I embarked on another trip with my university department at the very end of December. This was to be the first of three sequential field trips to the Judean Desert with Dr Dvir Raviv, each of the days dealing in turn with the northern, central and southern regions of the desert.

Looking out over Tariq Abu George

Being as this was the first day, our first destination was a small hillock overlooking Tariq Abu George, an important road that was paved by the Jordanians on the remains of an old Roman road. It was named after British army officer Edwin G. Bryant, previous superintendent of the Akko prison, who was nicknamed “Abu George” by his Arab admirers.

Golden eagle being mobbed by a common raven

The reason we were visiting this hillock was to take note of the geographical divide between the southern end of Samaria, and the subsequent start of the Judean Desert. While we surveyed our arid surroundings, I made note of some bird activity around me. First, I spotted a pair of buzzards far off over a ridge to the west, and then a small flock of alpine swifts. Next, much to my surprise, I noticed two somewhat rare golden eagles being mobbed by a few gregarious northern ravens. I had only ever seen golden eagles twice before – and both of those had also been on field trips with Dr Raviv (HERE and HERE)!

Hiking in the direction of Doq

Hiking back down the hill to our bus, we then headed for our first real destination of the day, the Hasmonean fortress of Doq. However, getting there was no small challenge, and our bus took a meandering route that led us through a Magav (Israel’s gendarmerie) training base and subsequent firing zones. As we drove I looked out the windows and noticed quite a nice amount of great grey shrikes, black redstarts and other birds. At last, our bus reached the vicinity of Doq and we all got out for a nice hike.

Under the watchful gaze of the Arabian green bee-eater

Overlooking the ancient city of Jericho, Doq was built during the Hasmonean period, and served as a fortress commanding the region. According to the Book of Maccabees, it was built by Ptolemy son of Abubus, the local governor appointed by Antiochus VII Euergetes, ruler of the Seleucid Empire some thirty years after the story of Hannukah. While the land was still in conflict between the different regional players, Doq was depicted as being the site of treachery against the Hasmoneans during a power struggle over Jerusalem.

Making our way to Doq

Our visit to Doq (also referred to as Dagon by Josephus) began alongside the dry Wadi el-Mefjer, where an Umayyad-built dam once stood to keep the seasonal flooding from destroying the crops down in the vicinity of Jericho. We hiked up and down the rocky slopes of the Qarantal ridge as we approached the first lookout, where we were able to survey our surroundings.

Approaching Doq from the southwest

From the lookout we pressed onward, climbing the zigzagging path that leads to Doq. Along the way we could see the restored Qarantal Monastery, also known as the Monastery of the Temptation, which was built on the cliffside overlooking Jericho. The monastery was initially built during the Byzantine period, when monasticism swept through the arid regions of the Holy Land, and then rebuilt in 1895 by the Greek Orthodox Church.

The more recent ruins atop Doq

At last we reached the peak and we entered the ruins of Doq via a small, yet enchanting doorway that provided a break in the long western wall. However, these ruins were not of the original Doq, but rather also part of a revival attempt by the Greek Orthodox Church in the late 1800s.

Corinthian capstone from the original Doq

Within, we saw that there was a large rectangular area, marked by a cross-shaped collection of low walls, and a series of arched rooms along the southern wall. We climbed to the roof of the rooms and took in the magnificent view that spread out before us of Jericho and the Qarantal beside us.

Dr Dvir Raviv backdropped by ancient Tel Jericho

Dr Raviv then gave us an geological survey of the surrounding area, and pointed out the various archaeological landmarks in the city, including the original Tel Jericho, the Shalom Al Yisrael Synagogue, the Herodian hippodrome, an Early Islamic sugar mill and other sites.

The large cave complex of the Qarantal

Turning to the Qarantal ridge, he then pointed out a series of caves marking the craggy cliffside. These were the Caves of the Spies, where it is believed the Israelite spies of the biblical story of Jericho had fled to, as well as other caves that were used in antiquity.

Inside the vaulted rooms

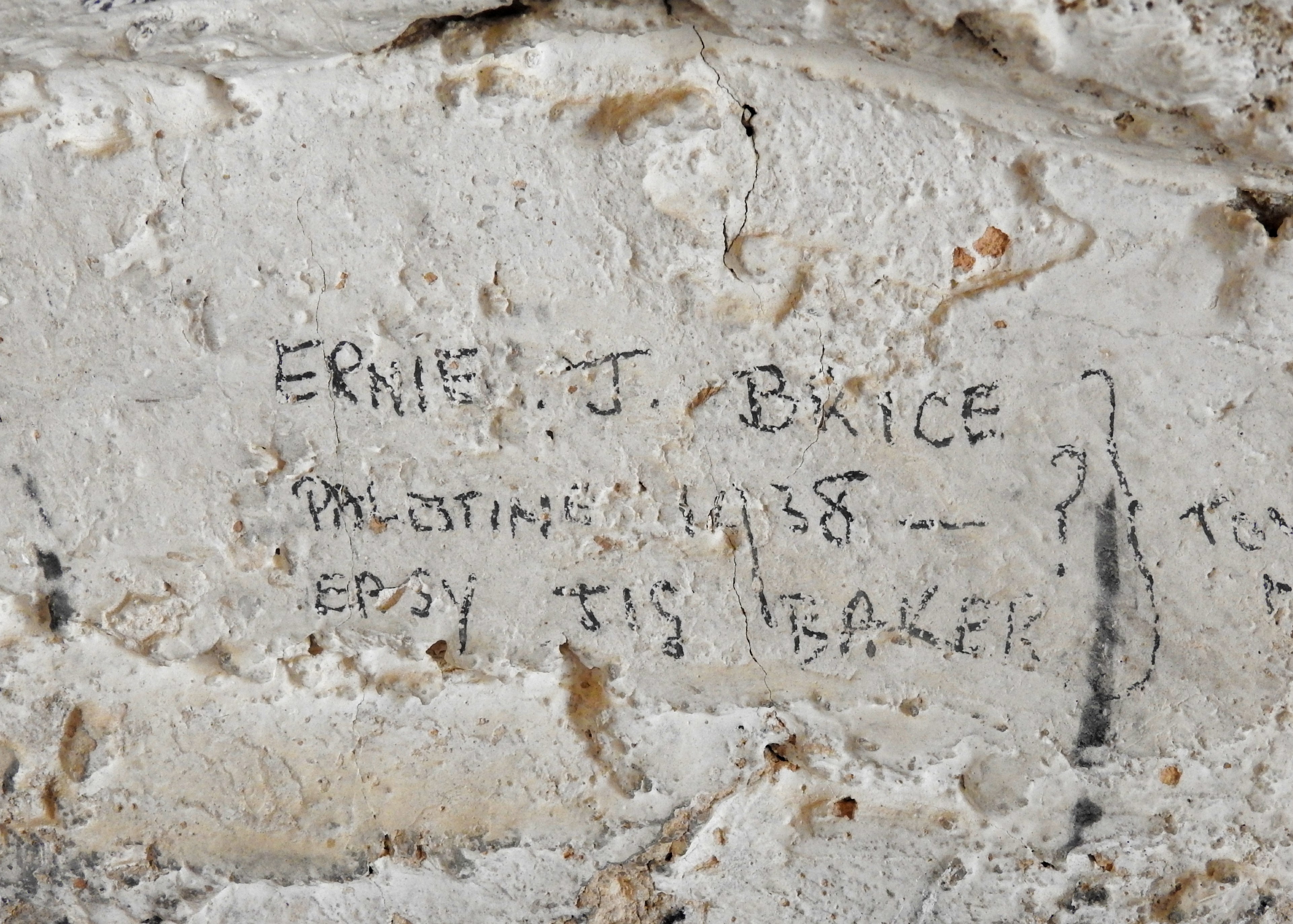

Wandering off to explore the vaulted rooms below us, I found something that intrigued me greatly. Upon the stone walls were written the names of past visitors, many of which were either in Arabic or in plain English. Some of the English graffiti was clearly signed by British soldiers who were likely stationed in the country. One particularly legible scrawl was by one Ernie J Brice, noting his time in Mandate Palestine from 1938 until unknown.

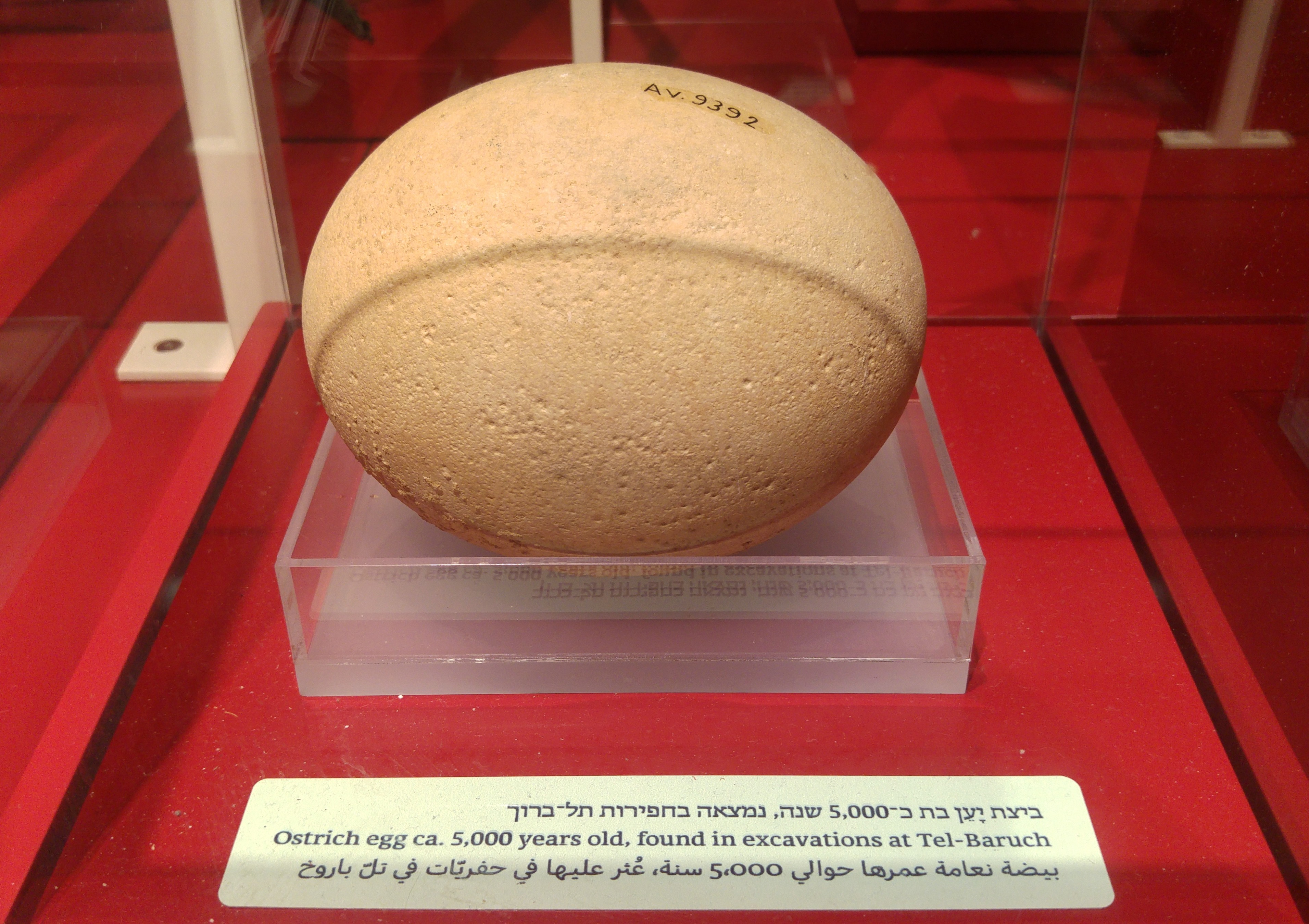

Graffiti left inside Doq’s lonely rooms

I happened to search this name and found that apparently he was the transmitter operator at the British consulate when Israel was established. His name came up in a 1948 Palestine Post write-up about Israel’s first espionage case, the fledgling government against a British citizen named Frederick William Sylvester who was spying for Israel’s enemies (see more HERE and HERE).

Hiking down to examine the water system

We then explored the remains of the to-be Greek Orthodox Church which incorporated what it believed to be a key shape in the construction, with scattered regal column capitals that bear testament to the grandeur that once was two thousand years ago. From there we left the confines of the wall and began to explore the ancient water system that joined a hewn channel with numerous cisterns.

Walking along the water channel on the eastern slope

Clinging to the craggy cliffside, we walked down the channel and examined the hard work that it took to create such an intricate system in such an arid place – only discovered in 1972. That, and the increasingly breathtaking views of Jericho spread out before us, with the aforementioned Qarantal Monastery just below.

Peering inside one of the system’s cisterns

Hiking the way back was via the same channel, continuing along the northern slope until we reached the adjacent ridge where a practically indiscernible small fort crowned the peak. We stopped there to catch our breaths, looking back at Doq and the areas we had just hiked. Refreshed, we then hiked back to the bus to be shuttled to our next destination of the day.

Hiking up to the small fort

Arriving at a place that I have had my eyes on for years, I was eager to get out and explore. We were at the Good Samaritan Museum, a mosaic museum housed on the ruins of a 2,000-year old wayfarers station, and later as a Byzantine-era inn from where its name originates. I had seen the museum site back in early 2018 when I had visited Castellum Rouge, a Crusader fortress built just across Road 1, and now was its time to shine.

The Good Samaritan Museum

Immediately inside the site’s gates we saw the showcased underground dwelling cave that dates back to the Second Temple period as well as a grand mosaic from the ancient synagogue at Gaza featuring a fine collection of artistic fauna. Many, if not all of the mosaics on display at the museum are those found in archaeological sites that wouldn’t otherwise be able to support the conservation on-site. Thus, when need be, the Israel Antiquities Authority systematically transplants and preserves these fragile works of art to be displayed for all.

The outdoor exhibits of the museum

It’d take a long time to list all of the magnificent mosaics that I saw that day, but there are some that stand out for several reasons. The mosaic that excited me most was the one found at Khirbet el-Lattatin, an interesting site just a kilometre or so away from my parents-in-law’s home in Givat Ze’ev. But there were those that impressed with their sheer beauty, such as the mosaics of the church narthex and the Roman fortress at Deir Qal’a, both stunning in their geometric patterns.

The Roman fortress floor from Deir Qal’a

These were all part of the outdoor exhibits, where mosaics are incorporated among the ruins of structures from the Second Temple and Byzantine periods, as well as a water cistern from the Crusader period. I enjoyed seeing capitals from Nabi Samuel, as well as hewn sarcophagi from Shechem (Nablus), but I was also eager to see inside the museum’s central building, originally built during the Ottoman period to serve as a police station guarding the treacherous road outside.

Capitals from Nabi Samuel on display

Entering, and rejoicing in the respite from the cold winds outside, I quickly became overwhelmed at the sheer quantity of mosaics on display. The six consecutive rooms, each full of mosaics and other accompanying artefacts, was almost too much to be properly enjoyed in one brief visit. Some did stand out, especially the inscription mosaic from the aforementioned Shalom Al Yisrael Synagogue in Jericho.

The eponymous mosaic from the Shalom Al Yisrael synagogue of Jericho

During the Byzantine period, when mosaic floors became an integral component to religious structures, the art was used by all faiths. I became impressed with the quantity and quality of the Samaritan mosaics, hailing from sites such as Mount Gerizim, El-Khirbe and Sha’alavim. However, it was the Samaritan synagogue at Khirbet Samara that took the proverbial cake, the mosaic remains showcased in a large glass-walled room.

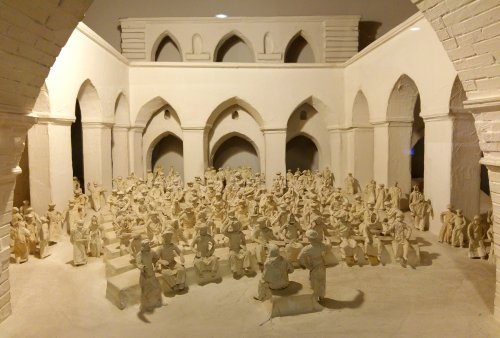

Within the room dedicated to Khirbet Samara

I looked around until it was time to get back on the bus for one last stop. The sun was slowly sinking, and Dr Raviv had one last place he wanted us to see before bringing this first field day to an end. Thankfully, it was not far and before we knew it, we were back outside again and climbing up a short hill to an excellent observation point looking out over Wadi Qelt and the Monastery of St George.

Ending our day at the Monastery of St George lookout

Evening was setting over the picturesque desert, marked by a flock of alpine swifts calling overhead as they welcomed the dusk. Plus, to boost our high spirits even more, a tiny birthday celebration for one of the students was held. The enchanting calls of Tristram’s starlings echoing in the wadi was our last audible memory of the day, accompanying us as we scurried back to our bus for the long ride back home.